When tasked with finding a manuscript on which to write my History of the Book project, I was stumped. Other than browsing facsimiles online, I’d never worked with archival material before – the prospect was exciting, but also daunting. While most of the course had been geared towards medieval manuscripts, I’m an early modernist focusing on eighteenth-century French literature – the manuscripts available to me were nowhere near as ornate as those chosen by my peers. As I looked at their thirteenth- to fifteenth-century manuscripts boasting gold foils, illuminated initials and colourful cartoon animals, I thought to myself: how am I going to find anything as exciting as this for my project?

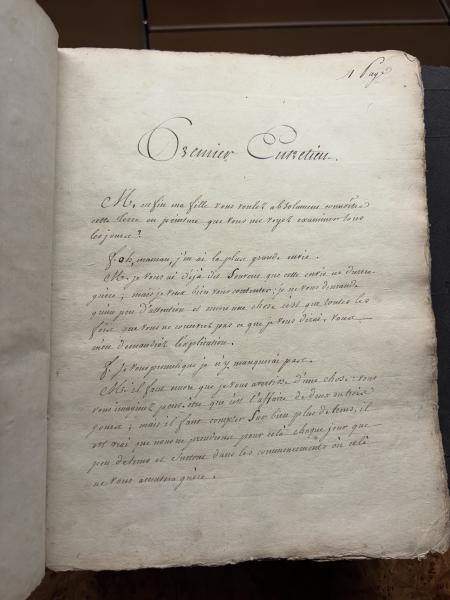

That was when, with the help of the Bodleian’s French librarian, I discovered my manuscript: an uncatalogued, unpublished collection of fourteen dialogues between a mother and daughter, written in 1771. Referred to as entretiens, these dialogues, in which the mother teaches her daughter about the world, are of a pedagogical nature. The lessons are incredibly sweet, with the daughter asking questions such as, “If the Earth is round, are there people walking upside down?” The mother begins with the solar system, explaining to her daughter that the Earth revolves around the Sun (a good start, if you ask me). She then progresses on to an incredibly detailed tour of the world, describing mountain ranges and rivers.

I chose this manuscript for several reasons. It was perfectly aligned with my research interests – having written my undergraduate thesis on women’s education in eighteenth-century France, I felt well-equipped to discuss the context of the work. In terms of materiality, the manuscript is beautiful; the pages have deckled edges, are bound in contemporary marbled boards, and the text itself is stunningly calligraphed in a uniform secretary hand. Hidden within the pages can be found adorable watermarks of griffins which were so much fun to find (see the picture)! But most importantly, I chose this manuscript because we know virtually nothing about it. Who is the author? Where was it found? Was it intended to be published?

Such were the questions I had to tackle in my project – but with only the manuscript itself to go with, I found myself a little in the dark. Nobody else had written about my manuscript, and, to my knowledge, it was the only copy – I’d come across it by chance, and it was my job to find out as much as possible about it.

My project had three sections: transcription, coding, and analysis.

Learning to read the script was the first stage: differentiating between ‘F’ and the long ‘S’, deciphering unstandardised spellings, and understanding the scribe’s erratic use of accents and capital letters. As the text had never been transcribed before, I took it upon myself to create a diplomatic transcription and a critical edition. For the diplomatic transcription, I replicated the text exactly as it appeared on the page – this part required lots of careful reading, to make sure that I copied the scribe’s spellings exactly. Luckily, my supervisor kindly checked my transcriptions for me – early modern palaeography is far from easy to learn, but after hundreds of pages of swirly letters, I got the hang of it.

Preparing the critical edition was one of my favourite parts of the project – I had free rein to standardise and punctuate the text however I saw fit, and add footnotes where necessary. This is where I really felt the text come to life on the page – all of a sudden, it looked professional and scholarly!

The coding was a whole different matter – as a humanities student, I was horrified by the prospect of learning to code! Thankfully, it wasn’t as complicated as I’d expected, and, when finished, will allow me to create a digitisation of the text, so it can be viewed by scholars and students online. Digital editions also have capabilities that physical editions lack; in my digital edition, I have tagged all people and place names mentioned, provided extra historical context where necessary (including links to relevant Wikipedia pages) and even tagged the mother and daughter as speakers, making names clickable and the dialogic structure even clearer. This task taught me the value of the digital humanities – a digital edition has the power to turn an uncatalogued manuscript at the Bodleian into a worldwide resource!

The analysis of the text itself, however, is where my project really came to fruition. The text is strikingly reminiscent of Louise d’Épinay’s Les Conversations d’Émilie: a well-known eighteenth-century educational treatise. Similarly to the manuscript, d’Épinay’s work is divided into several dialogues between a mother and daughter, which are also described as entretiens. D’Épinay has been credited both with establishing eighteenth-century ideas surrounding the mother’s role in her daughter’s education, and with using props in her dialogues: all of which my manuscript does too! But here’s the catch: Les Conversations d’Émilie was published in 1774 – three years after our manuscript was written! Has the novelty of d’Épinay’s work suddenly been undermined by the discovery of another series of mother-daughter dialogues written three years before it?

Unfortunately, I didn’t end up discovering who the author is, where the manuscript was found, or whether it was intended to be published. But what did I discover?

From references to Parisian locations such as the Tuileries Garden, I deduced that the dialogues were set in Paris – maybe the text was written there too. Through watermarks found on the paper, I know that the paper itself was produced in 1769 in Alençon. Given the very few corrections made to the text, I have assumed that it is a fair copy (rather than a first draft). I like to think that the author, if not also the scribe, is a woman – I have no evidence for this, but there is no way of knowing otherwise!

As an aspiring rare books and manuscripts specialist, the opportunity to work with an uncatalogued and unresearched manuscript offered the perfect mix of challenge and excitement. The thing I enjoyed most about this project, however, is the idea that in 1771, a scribe sat at her desk with a feather quill and wrote out fourteen entretiens, a collection of sweet conversations between a mother and her daughter. At a time when women were still discouraged from studying such subjects, the author demonstrated an impressive level of scientific and geographical knowledge, before putting her manuscript on a shelf where I would find it over 250 years later.